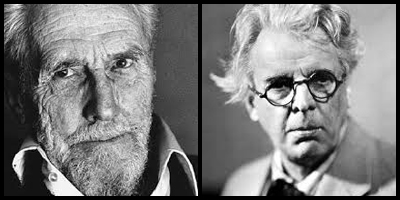

Yeats and Pound, though not exclusively a double act, can be looked upon as an occasional double act, as Pound and Eliot sometimes are. Their decade-long collaboration in London was fruitful and influential, and their friendship lasted at least another decade.

Yeats was the sorcerer, Pound the sorcerer’s apprentice. The ever-tasteful Pound had, from America and Italy, singled out Yeats as the first poet in the English language, a mantle the Irishman is thought to have inherited from Rudyard Kipling at some point in the early 20th century, certainly by 1912 when the observation was made by Robert Frost.

Pound became a Londoner in 1908 because Yeats was a Londoner, and sought to cultivate Yeats as friend and mentor. He succeeded quickly by making contact with Yeats’s former mistress Olivia Shakespear. He soon became a controversial fixture at Yeats’s Mondays at Woburn Buildings. Horton, a visionary friend of Yeats, imagined Pound entering with a pack of phantom-like black dogs on a leash. Later, Pound married Dorothy Shakespear, Olivia’s daughter, and Yeats married George Hyde-Lees, Dorothy’s best friend. Yeats and Pound were virtual in-laws.

As poets, the mentorship worked both ways. Pound hauled Yeats forward in modernity, but Yeats was the very embodiment of the eternal spirit of poetry. Pound’s Imagism was partly sourced in Yeats’s Symbolism. From a Yeats essay, ‘The Symbolism of Poetry’:

…we would cast out of serious poetry those energetic rhythms, as of a man running, which are the invention of the will with its eyes always on something to be done or undone; and we would seek out those wavering, meditative, organic rhythms, which are the embodiment of the imagination…

Yeats was impressed by Pound’s personality and scholarship more than by his poetry. But there was one poem that the Irish poet found arresting and that he cited again and again. Yeats saw it as a persuasive free verse workout and perfect Imagism.

THE RETURN

See, they return; ah, see the tentative

Movements, and the slow feet,

The trouble in the pace and the uncertain

Wavering!

See, they return, one, and by one,

With fear, as half-awakened;

As if the snow should hesitate

And murmur in the wind,

and half turn back;

These were the “Wing’d-with-Awe,”

inviolable.

Gods of the wingèd shoe!

With them the silver hounds,

sniffing the trace of air!

Haie! Haie!

These were the swift to harry;

These the keen-scented;

These were the souls of blood.

Slow on the leash,

pallid the leash-men!

It is one of Pound’s more enigmatic early works. Who are these characters? It is neither set in the contemporary bohemia of ‘The Garret’ or the medieval landscapes of Provence. Some see it as paganism, a depiction of the return of the pagan gods after the crisis of Christianity in the 19th century. They are Greek gods most likely. But there is no explanation as to why they seem so aged and infirm. The modernism to come would be almost over-dependent on Greek parallels seen as having more vitality than these ‘slow’ personages. Pound is a critic of the Judeo-Christian, but here implies the limpness of the new paganism. They seem like the survivors of an expedition to the antarctic. They also call to mind the poets of the 1890’s whom Yeats called ‘the Tragic Generation’: Davidson, Johnson, Dowson and others of the Rhymers Club and the Decadence, some of whom were dead, some of whom were alive but struggling, such as Arthur Symons. But really the poem is a parable. It is a strange elegy, an elegy for survivors.

For Yeats, it possessed occult qualities, so much so that he even reprinted it in his own occult manifesto A Vision. In 1913, he penned a reply.

THE MAGI

Now as at all times I can see in the mind’s eye,

In their stiff, painted clothes, the pale unsatisfied ones

Appear and disappear in the blue depths of the sky

With all their ancient faces like rain-beaten stones

And all their helms of silver hovering side by side,

And all their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more,

Being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,

The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.

But herein is an obvious twist. I identify Yeats as a Christo-pagan poet, and one of the most original Christian poets ever. Ireland has produced many Christian poets, but Yeats is utterly different to any. His unique take is due to his Rosicrucianism. A member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society, he communicated his spirituality to his readers in the compilation of early poems under the consecutive headings ‘The Rose’ and ‘Crossways’.

‘The Magi’ is very ostensibly not a pagan poem, like Pound’s, but a Christian poem, one whose subject is arguably the very first Christians on record, the three magician-kings who sought out the infant Jesus at his birth. But something is different; this is not like Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi’; it is more like a return journey. They too are suffering. Alchemical silver paints the scene. The crucial detail – literally the crux – is that the magicians are ‘unsatisfied’. The phrase is used twice. In the penultimate line it is revealed that they are unsatisfied by ‘Calvary’s turbulence’. So, they have witnessed the crucifixion. Therefore these mysterious travellers are attempting to journey from the scene of Christ’s death back to the scene of Christ’s birth. The brilliant final line “The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor” – reminding us of the later and more famous “Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born” – takes us unmistakably to the manger.

But Rosicrucianism tends to be more Rose than Cross. These magi also seem to be figures from Yeats’s own life, actual magicians, fellow initiates of the Golden Dawn. This was Yeats’s ‘church and university’, one he attended for almost three decades. His fellow seekers were on a serious quest for knowledge, and power. The head of the order had at the time of Yeats’s initiation in 1890 been Samuel Liddel MacGregor Mathers, charismatic author and ritual magician. Yeats had met him at the British Museum, struck by his heroic appearance, an appearance that seems to be recreated in the poem. Mathers was literally a magus, and a flamboyant eccentric. He and his wife Moina Bergson – sister of Henri the philosopher – designed the Vault of the Adepti. This was like a little self-contained room, moveable, a room within a room. It was supposedly modelled on the tomb of Christian Rosenkreuz and was beautifully decorated with images painted by the gifted Moina. The most famous image of Mathers is from a painting by Moina, capturing him in Egyptian looking attire. He was known to perform rites of Isis. The temple he, Yeats et al attended was the Isis-Urania Temple. Yeats seems to have immortalised the now lost Vault in another mysterious poem ‘The Mountain Tomb’ with its refrain “Our Father Rosicross is in his tomb.” The mountain in question is undoubtedly Calvary, a Yeatsian obsession.

But something else is at stake in both ‘The Return’ and ‘The Magi’. There is in both poems an imaginative vision at work, a vision of the procession, a poets’ equivalent of the artists’ tableau. Similar to the vision of a procession William Blake experienced as a teenager in Westminster Abbey – a procession of monks walking up the aisle – Pound’s and Yeats’s poems contain in their visionary vessels a procession of Greek gods and of ‘stiff figures’ respectively. Yeats even paraphrases Blake when describing these types of figure. Blake’s anti-establishent views are summed up in a phrase from A Public Address: “Princes seem to me to be fools. Houses of Lords and Houses of Commons seem to me to be fools. They seem to be something else besides human life.” Yeats adapted this avant-Ickean insult in a different way. He began using the phrase ‘something other than human life’ to describe these visions which he could see in the blue of the sky.

One of the members of this procession was a human being however. The excellent footnotes by Daniel Albright to the Everyman edition of Yeats’s poems point out that in Yeats’s unfinished novel A Speckled Bird, a character based on Mathers likes to wear a tattered crown and ermine rug while pretending to be one of the biblical magi.

Another story told by Roy Foster is of Maud Gonne’s snobbish reaction to encountering the Golden Dawn, whose shabby middle-class clothes she could see protruding from under their magical costumes: “They’re an awful set.” Mathers’s riposte was classical. “They said the same thing about the early Christians.” This is an exchange that Yeats could not have forgotten and his poem about the Christian magicians seems like an advance elegy for Mathers. Later, in his seance-poem ‘All Souls Night’ he conjured another more condescending vision of Mathers:

I call MacGregor Mathers from his grave,

For in my first hard spring-time we were friends,

Although of late estranged.

I thought him half a lunatic, half knave,

And told him so, but friendship never ends;

And what if mind seem changed,

And it seem changed with the mind,

When thoughts rise up unbid

On generous things that he did

And I grow half contented to be blind!

He had much industry at setting out,

Much boisterous courage, before loneliness

Had driven him crazed;

For meditations upon unknown thought

Make human intercourse grow less and less;

They are neither paid nor praised.

but he’d object to the host,

The glass because my glass;

A ghost-lover he was

And may have grown more arrogant being a ghost.

Moina Mathers was also furious with Yeats’s account of her husband in his autobiographical essay ‘The Tragic Generation’, calling the portrait “fantastic and grotesque”. Yeats edited offending details out of a subsequent edition.

Yeats and Pound, despised to this day by many, got away with much. Yeats got away with more, while Pound became a notorious pariah. Yeats didn’t live to see Pound’s disgrace, but would almost certainly have rallied to his defence, as he did with Wilde. Before Yeats and Pound fell out – Pound used the word ‘putrid’ to describe a new play by Yeats – they had once compared one another to Greek Gods. Pound thought of Yeats as Zeus; Yeats apologised to a friend for Pound’s brashness by calling him Hercules.

Niall McDevitt

http://www.nytimes.com/1988/01/10/books/the-odd-couple-pound-and-yeats-together.html